There’s a jazz club where a band plays John Coltrane’s Blue Train every Saturday night. No one knows about it. The place is dark and sticky but smells pleasantly of rum, cedar wood and sun-kissed sweat coming from the skin of its patrons. Among themselves, they have experienced the full depth of human experience, including death. All they do there is listen to the music and dance.

I go there wearing a yellow summer dress and no underwear. I don’t know what I look like but I know that the silhouette the yellow dress forms is, somehow, my true shape, especially when I dance and the dress spins. The spinning is detoxifying. It cleanses me of everything that isn’t core to me – destructive desires, dead-end worries, rubble that others have carelessly dropped off, and all the half-true stories I make myself believe. As we all spin to the music purifying ourselves, we generate a pulse which then spreads outside of the club, carries our scent, and makes all moving things oscillate to our rhythm.

But I don’t go to the dance floor straight away. I’m usually too exhausted to dance and can’t catch the rhythm. I feel ugly, old, stiff, and stuck. I worry about time and if I’m using it well when I’m there. What if I should just leave and forget the club ever existed?

Leaving is not so simple. I was warned multiple times that to quit would mean to betray everyone in the club, especially two old women who’ve been my main healers and persistently guided me through multiple little deaths and rebirths so I could join the dancing crowd.

The mysterious healing powers are not the only reason to keep coming. The other is company. Not only that I can talk to and dance with the wisest human and semi-human beings, they also care about me – in particular, they care about my needs, pleasures, desires and joy. I have a purpose, they insist, and for me to fulfil the purpose, I must “embody joy”.

As I had mentioned, the healing process involves a lot of dying. Even if this is beneficial and I do enjoy it, there’s only so much dying one can do, especially when everyday life gets busy. Around Christmas time last year, I began to grow frustrated with my commitments to the club, especially because joy was becoming a hard goal to achieve. I started doubting the importance of multiple rebirths and the club’s overall purpose: Perhaps feeling stuck is part of life, perhaps it builds humbleness? Could all this dying make me even stranger? Do I have time for this? And what if the patrons only care about me because they know a simple fact – if I stop coming, they will stop existing. Will I eventually have to leave and betray them?

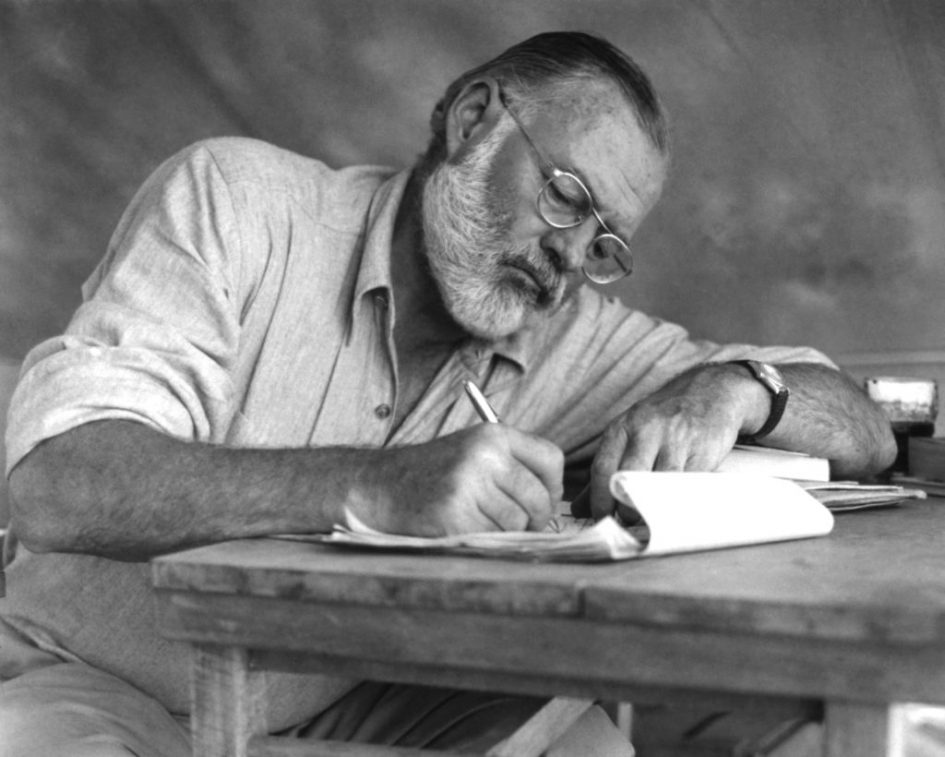

As I was sharing my doubts with the two two old women, an unexpected guest approached me. It was Ernest Hemingway. Although he was a regular guest in the club, we had never spoken. If fact, if there was one person in the club who seemed like he didn’t even notice me, not to mention care about me, it was Hemingway. He would just be there, joyfully drinking away the memories of war and his suicide.

He joined me at my table while everybody else was dancing in trance:

“You need to sit down at a laptop and bleed,” he said.

“But how,” I asked.

“Stop holding on to everything, let it out, push it out.” (He stressed the word “push.”) “Do not try to write like a man, not even like me. Reject writing like a man because you don’t bleed like a man. Men only know blood as a result of violence. Women bleed because it’s their fate. No violence needed, no peace possible.”

“I am bound to bleed from an open wound. And if I stopped bleeding, who would I be?” I said, continuing his thought but immediately questioned Hemingway’s right to give me advice.

“What do you know about a woman’s bleeding, Ernest? If anything, you’ve been a perpetrator of violence and pain?”

“I can’t speak for myself as Ernest Hemingway, but I can speak for the man you need me to be right now. I’m here to tell you how to bleed and how to write.”

I got suspicious as he started getting a bit closer: “This is weird, Ernest. Are you trying to seduce me?”

“Don’t doubt me, the writer you admire so much,” he said in a very confident way and reached under my yellow dress. “Let me show you a secret. You think pleasure comes with pain so you’re holding on to both, taking everything in. Instead, you need to let it out, push it all out until there’s nothing left. And then you’ll realise that you don’t have to worry about losing yourself, losing anything. You’ll feel true joy of creation. It already feels different, doesn’t it?”

It felt good, I had to admit that to him. Really good.

At the end of our intimate encounter, he gave me his shirt.

“No lover has ever given me his shirt,” I said.

He smiled in a cocky way and started listing things he would give me, if he could: a trip to Cuba, a dress and lingerie endowed with magical powers to make me feel sexy, beautiful and happy, a laptop to encourage me to write, and “some really valuable paintings”. The simplicity of his intention as well as the impossibility of his generosity made me cry.

“What do I do with this experience, Ernest?”

“Here’s a prescription for you, Doctor,” he said, still being cocky and flirtatious even as he was being serious. “You’ll keep coming here once a week and you will not betray us because, whether you like it or not, we are you. You know you’re not crazy. This club is key to you staying sane in this bloody place. You should write about it.”

Recent Comments